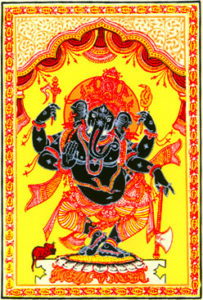

Ganesh, also known as Ganapati, is immediately recognizable as the elephant-headed god. He is the god of wisdom and learning, as well as the remover of obstacles, and consequently the sign of auspiciousness. It is customary to begin cultural events, for example, by propitiating Ganesh, and older Sanskrit works invoked his name at their commencement. Ganesh is said to have written down the Mahabharata from the dictation of Vyasa. He is the lord (Isa) of the Ganas or troops of inferior deities, but more well-known as the son of Shiva and Parvati. In the most common representations of Ganesh, he appears as a pot-bellied figure, usually but not always yellow in color. In his four hands, he holds a shell, a discus, a club, and a water lily; his elephant head has only one tusk. Like most other Indian gods, he has a ‘vehicle’, in his case a rat: this rat is usually shown at the foot of the god, but sometimes Ganesh is astride the rat.

Ganesh, also known as Ganapati, is immediately recognizable as the elephant-headed god. He is the god of wisdom and learning, as well as the remover of obstacles, and consequently the sign of auspiciousness. It is customary to begin cultural events, for example, by propitiating Ganesh, and older Sanskrit works invoked his name at their commencement. Ganesh is said to have written down the Mahabharata from the dictation of Vyasa. He is the lord (Isa) of the Ganas or troops of inferior deities, but more well-known as the son of Shiva and Parvati. In the most common representations of Ganesh, he appears as a pot-bellied figure, usually but not always yellow in color. In his four hands, he holds a shell, a discus, a club, and a water lily; his elephant head has only one tusk. Like most other Indian gods, he has a ‘vehicle’, in his case a rat: this rat is usually shown at the foot of the god, but sometimes Ganesh is astride the rat.

There are a number of stories about how Ganesh came to acquire an elephant head. Perhaps the most popular of these legends relates how Parvati, when she once took a bath, asked Ganesh to stand guard. When her husband Shiva wished to enter the bathroom [in other variants, it is the bedroom], he was opposed by his son; in his rage, Shiva cut off Ganesh’s head. Distressed by her husband’s enraged behavior, Parvati asked him to replace his head; and Shiva did so with the head of the first living being that he encountered, namely an elephant. According to a second legend, Shiva slew Aditya, the sun, but was condemned by the Vedic sage Kasyapa to lose the life of his own son in return; and when he replaced his son’s life, Shiva did so with the head of Indra’s elephant. Yet another story about the origins of Ganesh’s elephant head relates how Parvati, admiring of her son’s handsome looks, asked Saturn (Sani, from which is derived sanivar, or Saturday) to gaze at her son. But in so doing she forgot that the effect of Sani’s glance would be to burn the object he gazed at to ashes. In her distress, Parvati went to Brahma, who told her to replace Ganesh’s head with the first head that she could find. The sacred “Om” sign with which Ganesh is often associated points to yet another myth of his birth. According to this myth, one day Parvati saw the “Om” sign, and with her glance she transformed it into two elephants, from whose act of intercourse emerged Ganesh. They then resumed the form of “Om”, but ever since “Om” became known as the sign of Ganesh.

Though all Indian myths are subject to interesting psychoanalytic interpretations, the myths associated with Ganesh particularly lend themselves to some obvious psychoanalytic readings. Ganesh can be seen as competing with his father for his mother, and Parvati is herself, in some myths, seen as casting a far too admiring look at her own son; on the other hand, one can reasonably view Shiva as opposing the apparently incestuous relationship between his wife and their son. Shiva’s conduct towards his son Ganesh is of a piece with his conduct towards others who are viewed as being in sexual competition with him, when one recalls that he burnt Kama with his third eye and beheaded Brahma with the touch of his hand. In some myths, the beheading of Ganesh is replaced by the act of castration. The roots of Shiva’s violent conduct toward his own son may lie in the profound ambivalence he feels towards his own progeny. On the one hand, Shiva stands for fertility, and he is everywhere associated with the lingam or phallus; on the other hand, he is also the presiding god of ascetics. Consequently, Ganesh is, in a manner of speaking, his unwanted offspring.

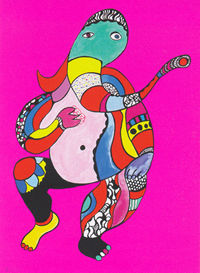

Ganesh remains, in many respects, among the most interesting of the Indian deities. Though the myths and legends attached to the figure of Krishna are immeasurably richer, no other Indian deity is as malleable, so amenable to creative, amusing, ironical, cubist, and three-dimensional representations, whether in painting, literature, or sculpture. There is no medium — stone, glass, cloth, paper, bamboo, wood, bronze, and numerous others — in which artists and craftspersons have not offered representations of Ganesh. He is unquestionably the most lovable and mischievous of the deities with his grandfatherly presence, his protuberant belly, and the twinkle in his eyes. Though there are many festive occasions on which Ganesh is honored, and he has an abiding presence in many Hindu households, his devotees everywhere in India, and most particularly in the state of Maharashtra, celebrate the Ganapati festival with great fanfare. As this festival unequivocally suggests, even Ganesh has been politicized, but seldom is much wisdom shown when this god of wisdom is put to use by ideologues to further the political agendas of militant Hindus.

FURTHER READING:

Primary Sources: The myths about Ganesh are to be found in numerous puranas, such as Agni, Matsya, Padma, Skanda, and Vamana, but the Brahmavaivarta Purana offers the richest accounts.

Secondary Sources:

Coomaraswamy, Ananda. “Ganesa.” Bulletin of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts 28 (April 1928).

O’Flaherty, Wendy Doniger. Asceticism and Eroticism in the Mythology of Siva. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1973.

For a Czech translation of this page by Barbora Lebedová, please go to: http://www.bildelarexpert.se/blogg/2017/02/16/ganesh/.

For a Swedish translation of this page by Weronika Pawlak, please go to: https://www.piecesauto-pro.fr/blog/2017/05/22/ganesh/

For a Finnish translation of this page by Elsa Jansson, please go to: http://mysciencefeel.com/2018/10/30/ganesh/