Music has always occupied a central place in the imagination of Indians. The range of musical phenomenon in India, and indeed the rest of South Asia, extends from simple melodies, commonly encountered among hill tribes, to what is one of the most well- developed “systems” of classical music in the world. Indian music can be described as having been inaugurated with the chanting of Vedic hymns, though it is more than probable that the Indus Valley Civilization was not without its musical culture, of which almost nothing is known. There are references to various string and wind instruments, as well as several kinds of drums and cymbals, in the Vedas. Sometime between the 2nd century BC and the 5th century AD, the Natyasastra, on Treatise on the Dramatic Arts, was composed by Bharata. This work has ever since exercised an incalculable influence on the development of Indian music, dance, and the performing arts in general.

The term raga, on which Indian music is based, was first discussed at any length in the Brhaddesi, a work from the 10th century attributed to Matanga. In the 13th century, the theorist Sarngadeva, who authored the large work Sangitaratnakara, listed 264 ragas; by this time, the Islamic presence was beginning to be felt in India. Some date the advent of the system of classical Indian music as we now know it to Amir Khusro. Muslim rulers and noblemen freely extended their patronage to music. In the courts of the Mughal emperors, music is said to have flourished, and the composer-musician Tansen was one of the jewels of Akbar’s court. Though songs had traditionally been composed in Sanskrit, by the sixteenth century theywere being composed in the various dialects of Hindi — Braj Bhasa and Bhojpuri among them — as well as Persian and Urdu. The great poet-saints who chose to communicate in the vernacular tongues brought forth a great upheaval in north India and the bhakti or devotional movements they led gained many adherents. The lyrics of Surdas, Tulsidas, and most particularly Kabir and Mirabai would henceforth be set to music, and bhajans, or devotional songs, continue to be immensely popular.

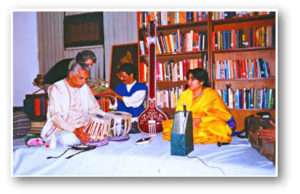

By the sixteenth century, the distinction between North Indian (Hindustani) and South Indian (Carnatic) music was also being more sharply delineated. Though music in the north, owing to the strong Muslim presence, had been more open to outside influences, in the eighteenth century South Indian musicians were to show themselves as being quite adept in adopting foreign instruments. Sometime in the mid-eighteenth century, the violin entered the repertoire of South Indian music, an instrument which in the late twentieth century has a dazzling array of extraordinarily brilliant performers. Classical music, both Hindustani and Carnatic, may be either instrumental or vocal: the connoisseurs of music maintain, as one might expect, that the vocalists represent the music in its greatest glory, but instrumental music has at least just as large a following. Though traditionally this music would have been performed in temples, courts, residences of noblemen and other patrons, and in small gatherings (called baithaks) of music aficionados, today most classical music concerts are held in concert halls.

In the 1960s, classical Indian music entered a new phase. It found adherents in the West, and the sitar of Ravi Shankar was to be heard on the famous Beatles’ album, Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band. Ravi Shankar, along with other well-known musicians like the Sarod maestro Ali Akbar Khan, was to make his home in the United States, and for the first time Indian classical music began to acquire Western students. Satyajit Ray, the first Indian director to acquire world fame, and a common name in repertory art cinemas, also brought classical Indian music to the attention of Westerners, for the music of some of his early films was composed by Ravi Shankar and Vilayat Khan, sometimes described as India’s greatest sitarist. Finally, collaborations ensued between Indians musicians and Western musicians, as in the case of Ravi Shankar and Yehudi Menuhin, who collaborated on a number of East-West albums. In recent years, Ravi Shankar has collaborated with the American minimalist composer, Philip Glass, on Passages; there have also been successful collaborations between L. Shankar and L. Subramaniam, both violinists, and Western musicians. This music is now routinely described as fusion. Though a musicians such as Ravi Shankar can scarcely be described as a household name in the West, he is unquestionably one of the most well-known non- Western musicians in the West, and Indian classical music can fairly be described as having carved a niche for itself in the world of concert music.

In India, however, music is most commonly associated with film music. Popular Indian films, whether in Hindi, Tamil, or any of the other Indian languages, are most often described and understood in the West as “musicals”, as they are seldom without songs, though they by no means constitute a genre as did American musicals. Also popular are ghazals, poetic compositions that aspire more than do popular film songs to poetic qualities: the subject here is usually the loss, memory, and remembrance of love. Qawaalis, compositions in which the subject is also love, though here it is understood that it is the love of man and woman for the Divine, have also attained a certain following, and in recent years the Pakistani qawaali singer Nusrat Fateh Ali Khan has established a world-wide reputation.